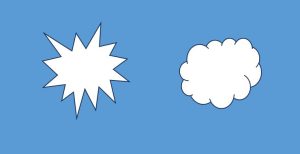

Look at the shapes depicted on the right. In a 2001 study on sound symbolism, VS Ramachandran and Edward Hubbard report that 95% of people pick the right image as kiki and the left as bouba. (Subjects are told the words are from a Martian language and are asked to guess what they might mean!). The researchers conclude ‘because of the sharp inflection of the visual shape, subjects tend to map the name kiki onto the figure on the left, while the rounded contours of the figure on the right make it more like the rounded auditory inflection of bouba’. They suggest that sound-object mappings are not entirely arbitrary, and that this phenomenon may even have contributed to the development of human language in the first place.

Look at the shapes depicted on the right. In a 2001 study on sound symbolism, VS Ramachandran and Edward Hubbard report that 95% of people pick the right image as kiki and the left as bouba. (Subjects are told the words are from a Martian language and are asked to guess what they might mean!). The researchers conclude ‘because of the sharp inflection of the visual shape, subjects tend to map the name kiki onto the figure on the left, while the rounded contours of the figure on the right make it more like the rounded auditory inflection of bouba’. They suggest that sound-object mappings are not entirely arbitrary, and that this phenomenon may even have contributed to the development of human language in the first place.

The mapping between sounds and objects was first documented in the 1920s by Wolfgang Köhler in experiments with Spanish speakers on the island of Tenerife (although he used the words baluba and takete). Ramachandran and Hubbard’s study demonstrates the effect among English-speaking US college students and Tamil speakers in India but, until recently, there was relatively little evidence as to how well the effect worked across a wide range of languages or different written alphabets.

In November 2021, Radio 4’s Inside Science programme featured an interview with a researcher who has looked in more depth at multilingual sound symbolism and the impact of orthography. Aleksandra Ćwiek of Leibniz-Zentrum Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft in Berlin reports on a study across 25 different languages with a wide range of cultures and orthographic systems. A total of 9 language families and 10 writing systems were included. The results confirmed the bouba-kiki effect across languages, with speakers of languages with Roman scripts only marginally more likely to show the effect. The researchers conclude that the phenomenon is rooted in a correspondence between features of speech and visual shapes and is largely unaffected by orthography.

A word of caution should be sounded about the study which is that the subjects were recruited via the authors’ own social networks. Consequently, the participants are not necessarily typical of the linguistic communities they represent. In particular, the respondents are likely to be more highly educated and 86% of those surveyed said they spoke a foreign language, with 80% citing English as either their first or second language.

With that caveat in mind, the researchers’ findings seem to tie in with earlier research on sound symbolism in young children, suggesting that written word forms are largely unimportant. In a 2006 study reported in Developmental Science, Daphne Maurer, Thanujeni Pathman and Catherine Mondloch found that 2.5-year-old children matched words with rounded vowels to rounder shapes and words with unrounded vowels to pointed shapes. They also draw the conclusion that such natural correspondences between sound and shape may influence the development of language.

About the Author

Alison Tunley

Alison is a seasoned freelance translator with over 15 years of experience, specialising in translating from German to English. Originally from Wales, she has been a Londoner for some time, and she holds a PhD in Phonetics and an MPhil in Linguistics from the University of Cambridge, where she also completed her First Class BA degree in German and Spanish… Read Full Bio